Tactical Analysis of Ralph Hasenhüttl’s RB Leipzig

Analysis from Bundesliga matches from the fall of 2017

Table of Contents

Part One

Introduction to RasenBallsport Leipzig

Path to the Bundesliga

Success in 2016-17

Introduction of Ralph Hasenhuttl

Part Two

Attacking Play

Counter Attacking

Organized Attack Play

Part Three

Without the Ball

Pressing

Organized Defending

Weaknesses

Part Four

Application at Youth Soccer level

Potential Benefits to Youth Players

Part One:

Introduction to RasenBallsport Leipzig

RasenBallsport Leipzig, more commonly referred to as RB Leipzig, was founded in 2009 when Red Bull GmbH purchased the playing right of a fifth division Club in the German soccer system. The Club was renamed and Red Bull GmbH announced they intended to have the team playing in the Bundesliga within eight years. Surrounded by controversy and loathed by nearly every other Club’s supporters in the country, RB Leipzig achieved this goal at the end of the 2015-2016 2. Bundesliga season.

RB Leipzig and Red Bull GmbH have had to battle numerous issues in conflict with the DFL(German Football League) since applying for a license to play in the 2. Bundesliga and Bundesliga after winning promotion from the third division, 3. Liga, which is controlled by the DFB(German Football Association). RB Leipzig had to change their badge as it was deemed too similar to Red Bull’s logo, both when the Club was founded and again to comply with the DFL.

The Club has also had to deal with the structure of it’s ownership and controlling members of the Club being associated with Red Bull GmbH. It is a complex situation and the off field story of RB Leipzig’s existence is at least equally as interesting as their on field journey. We will look only at the on field progression of the Club here.

RB Leipzig were able to win immediate promotion from the fifth division in 2009-10 winning the NOFV-Oberliga Sud with a 26-2-2 record. It took three seasons to get out of the fourth division with finishes of fourth, third and finally, first in 2012-13. In that time, RB Leipzig twice won the Saxony Cup, a regional cup competition for third division and lower Clubs, in 2010-11 and 2012-13.

The next two promotions came about much quicker, RB Leipzig spent one season in 3. Liga, 2013-14, that saw them finish in second with a 24-7-7 league record. Finishing second meant automatic promotion to the 2. Bundesliga, where the Club spent the 2014-15 and 2015-16 seasons. A second place finish in the Club’s second go around in 2. Bundesliga saw them finish with a 20-7-7 record and sent them up into Germany’s top flight for the first time.

RB Leipzig arrived in the Bundesliga having used six first team coaches, one interim, across the seven seasons it took to complete the ascension from the fifth division. Only one lasted longer than a year, Alexander Zorniger, who was in the job for 954 days starting on July 1, 2012 and ending midway through the 2014-15 season. Zorniger led RB Leipzig to back to back promotions in his first two seasons before being let go when the Club found themselves mid table in February.

In their promotion winning season of 2015-16, RB Leipzig’s Sporting Director, Ralph Ragnick, appointed himself manager and planned to take on the coaching position for only one season. The man eventually brought in to guide RB Leipzig in their first Bundesliga season was the Austrian, Ralph Hasenhüttl.

Hasenhüttl decided to join RB Leipzig after a successful three year spell in charge of FC Ingolstadt 04. Hasenhüttl was appointed there in October of 2013 with Ingolstadt bottom of 2. Bundesliga. He stabilized the Club and led them to a fifth place finish. In his first full season with the Club they won the 2. Bundesliga and were promoted to the Bundesliga. Hasenhüttl stayed on with Ingoldstadt for the 2015-16 season and took them to eleventh position.

RB Leipzig are the fourth Club, all German, that Hasenhüttl has been head coach of since retiring as a professional player in 2004, having begun his playing career in 1988. Aside from his 2. Bundesliga title, Hasenhüttl also won promotion from 3. Liga with Vfr Aalen in 2011-12. He made eight appearances for the Austrian national team between 1998 and 1994, scoring three goals.

From 1994 to 1996, Hasenhüttl spent two seasons playing with SV Austria Salzburg, who are now known as Red Bull Salzburg. Along with RB Leipzig and Red Bull Salzburg the Red Bull company also owns New York Red Bulls in MLS and Red Bull Brasil in Sau Paolo, Brazil. All of them except Red Bull Brasil have their home stadiums carrying the Red Bull Arena name. And only RB Leipzig do not have “Red Bull” in their official name.

Despite that, RB Leipzig are instantly recognizable as a Red Bull entity as they bare similar uniforms and, of course, have Red Bull as their principle shirt sponsor. RB Leipzig are now considered the crown jewel of Red Bull’s soccer entities as their presence in the Bundesliga, the highest ranked domestic league with a Red Bull Club, would suggest.

Several current RB Leipzig players have made their way to the Club from other Clubs in the Red Bull group. The Brazilian fullback, Bernardo, spent time with both Red Bull Brasil and Red Bull Salzburg before joining with RB Leipzig in 2016.

Red Bull Salzburg are clearly playing the role of feeder Club to RB Leipzig despite Salzburg being established in European competitions having featured in the Europa League group stages seven times since 2009-10. The transfer of players from Salzburg to Leipzig began before the German Club even reached the Bundesliga. Since becoming Red Bull Salzburg they have won the Austrian Cup five times and won the Austrian Bundesliga eight times and played twenty-three rounds of Champions League qualifiers.

Clearly, Red Bull Salzburg have been successful since their inception but it’s obvious that marketing a Club representing a global brand in the German Bundesliga is far more appealing than any Club in the Austrain Bundesliga. Especially so after RB Leipzig managed to make the group stage of the Champions League this season and are in a strong position to do so again next year.

RB Leipzig has the following current first team players formly from Red Bull Salzburg for this year’s campaign:

Player Year Joined

Bernardo 2016

Dayot Upamecano 2017

Marcel Sabitzer 2015(returned from loan to Red Bull Salzburg)

Naby Keïta 2016

Stefan Ilsanker 2015

Benno Schmitz 2016

Konrad Laimer 2017

Péter Gulácsi 2015

That list includes two players who made the switch before RB Leipzig had won promotion to the Bundesliga, joining in 2015, it suggests that even then the priority Club in the Red Bull group was Leipzig. The list doesn’t include Kevin Kampl who spent three years with Red Bull Salzburg from 2012-15, before moving on to Borussia Dortmund and Bayer Leverkusen, and then joined RB Leipzig at the start of 2017.

Going forward RB Leipzig should be considered among the most influential and powerful Clubs in Germany. The backing of Red Bull GmbH gives the Club tremendous potential for future investment. The Red Bull brand was ranked by Forbes Magazine as the 70th most valuable brand in the world and Red Bull products were sold in 171 countries in 2016.

Just this month, Soccerex published their “Football Finance 100” report focused on the economic power and potential of soccer Clubs across the world. RB Leipzig were ranked twelfth, one spot ahead of FC Barcelona. RB Leipzig came second among Bundesliga Clubs trailing only Bayern Munich, who themselves only slotted in at tenth. RB Leipzig were five spots ahead of BVB and their sister MLS entity, New York Red Bulls came in at twenty-third.

Soccerex cited the value of RB Leipzig’s playing squad, which they value as the twenty-ninth highest in the world, and the significance of Red Bull’s potential investment as the two biggest factors in their ranking. To see a Club in existence for not even a decade ranked ahead of FC Barcelona is an incredible statement on the state of modern global soccer. What type of force RB Leipzig will become in Europe remains to be seen.

Can they emerge as giants of Europe like PSG, Manchester City and Chelsea before them? Oil money fueling the rise of Clubs to new heights has been well established in Europe. Just how far an energy drink can fuel RB Leipzig’s ambitions, along with the feeder Clubs arrayed to help them, will continue to be of interest, and controversy, to many in the world of soccer.

Overview of Matches Analysed

For this analysis, seven consecutive Bundesliga matches played by RB Leipzig were utilized. These matches were played between November 4 and December 17, 2017. During this time, RB Leipzig played three Champions League group stage games including on Wednesday, November 1, three days before the first match in the analyzed selection of Bundesliga matches.

At the start on November 4, RB Leipzig held second position in the Bundesliga with a 6-1-3 record. At the conclusion, the last match heading into the winter break, RB Leipzig had dropped to fifth position having gone 2-3-2 in the seven matches. Thus, at the winter break RB Leipzig’s record stood at 8-4-5 and they were on 28 points, the same number of points taken by BVB, Bayer Leverkusen and Borussia Mönchengladbach. They sit two points behind Schalke 04, in second, and are thirteen points off the leaders, Bayern Munich.

In the selected matches, RB Leipzig scored eleven goals, while conceding twelve. They played four times at home and three times away facing Hannover 96, Bayer Leverkusen, Werder Bremen, 1899 Hoffenhiem, Mainz 05, VfL Wolfsburg and Hertha Berlin. RB Leipzig’s bigger defeat of the two was a 4-0 hammering against 1899 Hoffenhiem, the bigger of their two wins was a 2-0 over Werder Bremen. Those two matches represented the only ones in which one of RB Leipzig or their opponent failed to score, the other five matches all saw both teams score. There was an average of 3.3 goals scored per match in the seven match selection between both teams. RB Leipzig’s overall average of goals per match between both teams was 3.1 through the first half of the Bundesliga season.

RB Leipzig utilized a 4-2-2-2 formation, this shape was most visible in organized periods of defending. Their attacking shape was much more fluid and rarely, if ever, looked like a 4-2-2-2 at any point with the ball. RB Leipzig did use various movements to arrange themselves in a back three during organized periods of attack. This was never how they set out to play and they also utilized different ways of creating the back three based on the selected players.

In the selected matches, Péter Gulácsi, the goalkeeper, and Timo Werner, center forward, where the only two ever presents in the starting lineup. Yussuf Poulsen was selected alongside Werner at center forward in all but one match. The outside back pairing of Lucas Klostermann and Marcel Halstenberg were selected six times each, the Brazilian back, Bernardo, was selected when the two first choice outside backs were not.

In midfield, Diego Demme and Naby Keïta were selected five times each in deep midfield positions, while Kevin Kampl featured six times from the start in an advanced midfield position. The left advanced midfield position saw both Emil Forsberg and Bruma selected three times each. Forsberg is surely first choice, however he suffered illness in December.

RB Leipzig used four center backs in the seven matches, Ibrahima Konaté featured most often, five times from the start. Willi Orban and Dayot Upamecano made four starts each and Stefan Ilsanker stepped in for two appearances at the back. Konrad Laimer started twice in midfield, Dominik Kaiser once and Marcel Sabitzer missed a chunk of time due to injury, starting only twice.

Even with the presence of three midweek Champions League matches, one midweek Bundesliga match, and an international break necessitating rotation, along with injuries, sussing out Ralph Hasenhüttl’s preferred starting eleven isn’t too difficult. Gulácsi is first choice in goal, Klostermann and Halstenberg at right and left outside back, Demme and Keïta in deep midfield, Kampl and Forsberg at the advanced midfield positions and then Poulsen and Werner up top. The only difficult area would be his preferred center back pairing. Konate and Upamecano are teenagers and Orban is vice-captain, we will assume then that Orban, who usually plays on the right, would be selected with Upamecano who was usually fielded on the left.

Here then is RB Leipzig’s formation and assumed first choice eleven:

Terminology

For the purposes of this analysis, please keep in mind the following terminology. All references to a portion of the playing field are from RB Leipzig’s point of view, the half spaces, wide areas, attacking third, defensive third, all are from the point of view of RB Leipzig.

Generally, a great deal of analysis will be separated between discussing organized and unorganized periods of play both when RB Leipzig are attacking or are without the ball. The term “possession” may be used but please understand, for this analyst, any time a team has the ball, they are attacking, not possessing. This recent perception of looking at organized and unorganized periods of play can be attributed to an outstanding piece of work by Adin Osmanbasic. If you’ve not read it, please do(and then comeback here).

The back line players will be referred to as outside backs and center backs, the term “fullback” will not be utilized. The midfield four will be referred to as either deep or advanced midfielders. Terms like “holding”, “defensive”, “attacking” midfielder will not be utilized, nor will there be any references to numbers as positions. Apologies in advance if you have a preference for different terminology!

There is a good amount of complexity to RB Leipzig’s attacking play. The essential reason for this is the variety of off ball movement in attack from nearly every player on the field, aside from the goalkeeper and center back pairing. This fluidity is a necessity to create proper spacing and angles to the player with the ball, which is not an inherent feature of the 4-2-2-2 or the 4-4-2 it closely resembles. The 4-3-3 easily sets up like a 2-3-2-3 in attack and allows for strong connections between the lines due to the angles created. RB Leipzig have to work off their organized defensive shape a great deal more for this to happen.

Building Attacks from the Back

Starting from the most static position of the goalkeeper, Péter Gulácsi, there is a willingness to play from out back when afforded the opportunity, both from open play possession of the ball and goal kicks. When Gulácsi has the ball, in his hands or at his feet, both center backs(no matter which two) always made themselves available for balls played to feet. The center backs would position themselves inside the width of the penalty area and not much wider. They would not normally go into the wide areas beyond the penalty area near to the goal line. If the center backs were marked and in a 3v2 with Gulácsi, they would not look to play and instead would go long.

When RB Leipzig’s attack moved into the opponent’s half the center backs were most always positioned on the midfield line. Gulácsi was not used often once play had moved into the midfield third. On some occasions of being pressed aggressively, the ball would be played back to him in attempt to stretch the opponent vertically and begin another attack with short combination play.

Inside of their own half, a deep midfielder would usually be relied upon to position themselves to form a diamond with the goalkeeper and center back pairing, acting as the advanced tip of the diamond. This movement was lacking when Diego Demme was not on the field. Demme seemed to have the best understanding of when to come deep into this position. Stefan Ilsanker and Konrad Laimer would have been operating in deep midfield positions as well but their movement to help take the ball off Gulácsi was not as frequent.

Player Profile: Diego Demme

Diego Demme is in his fourth season with RB Leipzig, having joined them for the 2014 season when they were still residing down in 3. Liga. Demme is a twenty-six year old, German with one senior cap for the full national team last summer. For all the talk about RB Leipzig’s talented array of players, Demme certainly deserves more of a spotlight outside of Germany. As painful a comparison as this is for a Spurs fan, Demme’s physique and style of play resembles that of Arsenal’s Jack Wilshere(when healthy).

Demme is a superb technical player with a strong ability to control the ball in tight spaces, fight off pressure and is equally adept at short and long range passing. His movement in the first two thirds of the field in organized attack is varied and intelligent. As mentioned, Demme provided support in the central area in advance of the center backs for either the goalkeeper or center backs to play through the first line of pressure to his feet. When faced with an opponent dropping deeper, Demme operated in front of the first line of pressure well in central positions. He was able to start play moving forward and play out to the outside backs operating in the wide area whenever allowed to turn and face forward.

When forced from the central area in front of the center back pairing, Demme had a range of movement to find open space where he could face forward on the ball. He would recognize when to drop between the center back pairing and also made use of the half spaces to the left and right of the center back pairing. The half spaces and wide areas close to the center back pairing was usually not occupied as Leipzig rely on the outside backs for width in higher areas up field.

Demme’s positioning was consistently useful to his teammates when play had moved in advance of him as well. Just as he was able to form the tip of a diamond when the ball was deeper than him, he was also able to form the base of a diamond when play had moved beyond him.

Demme’s ability on the ball and range of movement to get on the ball allowed his deep midfield partner, usually Naby Keïta, to operate in more advanced positions. He also made it possible for the, sometimes, extremely forward positioning of RB Leipzig’s outside backs to develop. The adventures of RB Leipzig’s outside backs and Keïta’s attacking prowess are a crucial aspect of their attack play. Aspects that wouldn’t be possible without the quietly efficient Diego Demme.

In situations where Péter Gulácsi was unable, or unwilling, to play short, his preferred long option was to seek out Yussuf Poulsen, the six-foot-four center forward. In spite of Gulácsi’s ability to accurately target Poulsen and Poulsen’s height, RB Leipzig had mixed results with this tactic.

When Leipzig were able to get a midfield player behind Poulsen as he controlled a long pass they were able to successfully create some chances. Poulsen always looked to drop away from the opponent’s back line for these longer passes and Timo Werner, the other center forward, would look to stay high beyond him. On two occasions, Kevin Kampl was positioned to receive a layoff and play Werner in behind, one situation saw Werner hit the crossbar with a shot from range, the other, Werner was tripped from behind and the offending player was sent off.

Another good chance was created from this tactic from a layoff from Poulsen to Bruma that resulted in Werner tapping in a cross, albeit from an offside position. However, Leipzig would have had more success had they gotten numbers around Poulsen more efficiently. That’s a strong characteristic of Leipzig’s attacking play in most other situations. This tactic of going long from deep positions is definitely a plan B, or even a plan C, as Leipzig are always looking to counter attack or, in organized play, are prepared to utilize short passes in tight spaces to move forward. This third way not being effective is then understandable.

Limited Counter Attack Opportunities

RB Leipzig preferred to counter attack, allowing them to capitalize on unorganized situations to create chances on goal. However, this tactic was denied to them for large portions of the matches in this selection. Teams, it seems, would have learned from Leipzig’s first season in the Bundesliga how much of a threat they pose in counter attacking situations. This season teams have done an effective job of sitting deeper, staying more compact, limiting their numbers going forward in attack and avoiding losing the ball in their own half.

This adjustment from RB Leipzig’s opponents has forced them into far more instances of organized attacking play. This has caused them problems, both in scoring goals and also being exposed themselves to opponent’s counter attacks. It’s not an entirely dissimilar story to that of Leicester City’s Premier League title defending season. After shocking the whole of England with a title winning campaign built off of deadly counter attacks that opponents seemed reluctant to adjust to, they found themselves denied this in the following season and subsequently fell off as serious top four contenders.

RB Leipzig are unlikely to suffer a similar fate to Leicester City, however, they are being forced to deal with opponents denying them the counter attacking opportunities they desire. Of the eleven goals scored in the seven matches, only one was scored directly on a counter attack compared to three from corners, three penalties, one free kick and three from open play. All three penalties were won at the end of a counter attack, really then, four of their eleven goals were the result of a counter attack.

Organized Attack Play

Three goals in seven matches from open play shows that improvement is needed in this area for RB Leipzig going forward. They did display a good deal of promise and plenty of ideas in organized attack play and you would expect improvement to come from gaining more experience in these situations for a young team like Leipzig. Twelve of the twenty youngest starting elevens fielded in the Bundesliga this season have been Leipzig teams, they have an average age of just 24.3 years old.

The first trait of Leipzig’s organized attack play that stands out is how compact they are, both vertically and horizontally. Everyone on the field is comfortable with the ball at their feet in tight spaces and willing to play passes into tightly defended areas. Switches of play are rare, more so the further forward they move the ball, and they certainly could not be accused of playing around the back in a ‘U’ shape much at all, if ever.

RB Leipzig relies on fluid positioning in order to create the necessary angles to play through their opponent. This starts with the two deep midfield players, typically Demme and Keïta, making sure one of them is always in a deep, central position. This is usually, but not always, Demme, who allows Keïta to move forward and look for space between the lines or out into the half spaces to offer support. Demme’s positioning allows for Keïta to impact attack play with his dribbling ability and incisive vertical passing. It was rare for both of the deep midfielders to be positioned in a flat horizontal line with one another in any phase of attack play.

The two advanced midfielders formed relationships in their movement more with the outside backs than each other. Kevin Kampl, when played at advanced mid, was able to recognize quickly whenever the outside back was in a deeper position and the wide area in front of the back line needed to be occupied. Also, as in the picture above, when the outside back was pushed up in the wide area he offered himself for passes in the half space. Kampl would also come deep behind the first line of pressure to get on the ball as well if this space was left unoccupied by the deep midfielders, a more common occurrence when Demme was not fielded.

This tactic of the wide area being occupied by only one of the outside back or the advanced mid on the side of the attacking move was also carried out by Emil Forsberg and Marcel Halstenberg on the left side when both were playing. Only Bruma, with three appearances at the left advanced midfield position, seemed out of tune with this tactic. He operated more in a traditional wide midfield role regardless of the outside back’s position.

The relationship between the advanced mids and outside backs was an important component of forming diamonds in attack play in cramped spaces on one side of the field. They often formed the left and right sides of the diamond with a center forward and deep midfielder creating the tip and base. Poulsen was adept at positioning himself in the half spaces with his back to goal to form the tip of the diamond when needed.

Again referencing the picture above, and you’ll see it below again in a moment, the deep/advanced positioning of the deep midfielders helped to form diamonds. And the advanced midfielder was expected to recognize where he was needed, either in the half space or in the wide areas, based on the outside backs position to help create these situations. Below, Dominik Kaiser is in the wide area(playing advanced mid), as the outside back is in a deeper position and Demme is to the left of the ball carrier, Konrad Laimer(the deep midfield partners), Poulsen is showing back to goal, thus leaving the right open for Kaiser to fill in. Laimer plays Poulsen who back heels the ball behind him towards goal for Demme to run onto. Demme finds Kampl moving from the center for a sublime one touch shot in the left side of goal. Watch it here, one of Leipzig’s better goals in this selection.

The picture above also shows the large degree of freedom of movement afforded to the opposite sided advanced midfielder. Above, Kampl was the left advanced midfielder and was well into the center of the field for this attack coming up the right side. Forsberg was more adventurous in his movement when Leipzig attacked on his opposite side. He would operate in between the opponent’s midfield and back lines in central positions in the space normally filled by a “#10” playing between two wide midfielders and behind a center forward. Leipzig, of course, have only two players in the advanced midfield line, not three like you would find in a 4-2-3-1. This critical space behind the center forward needed to be occupied to take advantage of the center forward’s runs in behind pulling center backs into deeper positions.

Poulsen would drop from his center forward position into this space for attacks through the center but he also made many movements into the right half space for right sided attacks, thus leaving the space to be filled by Forsberg. He was also willing to drop into deeper areas or come all the way over to the right side of the field to support attacks. When doing so, he would leave the outside left back, Marcel Halstenberg, completely alone on his side of the field, and even he might only be as wide as the left half space.

Attack Play from the Outside Backs

The attacking positions taken up by the outside backs could be extremely high and well in advance of the ball position. Lucas Klostermann, on the right, and Marcel Halstenberg, on the left, contributed to all manner of attacking situations for RB Leipzig. They were least involved when Gulácsi or the center backs had the ball in deep in their own half, even at this stage of attack they were expected to be positioned in more wide midfield areas. This was a necessity, given the more central movements of the advanced mids, in the creation of width.

If play moved to either the right or left side, which it usually did to try and create overloads against the opponent, the opposite sided outside back would actually come narrower into the half space from a wide position. That meant even the occasional switch of play from Leipzig was only to the extent of playing from the center into the opposite half space or one half space to the other. It could be effective though as Leipzig’s determination to create an even or up numbered situation in tight spaces would draw the opponents into horizontal compaction themselves. This often left the opposite side outside back with ample room to advance forward on the dribble.

Bernardo, who only featured from the start twice, was the second option at either outside back position. He did start at left outside back against Mainz 05 and was the principal player staying deep to form a back three in organized attack. This was in a match that did not feature Keïta from the start, which was significant because Konrad Laimer came in for him along with Demme. However, Demme deviated from his usual role of staying in deeper positions to allow Keïta to move freely in more forward positions. Instead, Demme gave a convincing impersonation of Keïta’s usual attack minded play with vertical dribbling and passing breaking lines in central areas. It was a wonderful adaptation of role by Demme, perhaps a preview of how life without Keïta will be for Leipzig.

What’s this got to do with Bernardo creating a back three? Well, Laimer’s impersonation of Demme’s deeper role was not as convincing as he did not come into deep positions in front of the first line of pressure as consistently as Demme, nor did he drop into the back three. This could of been by design from Hasenhüttl, it’s unlikely though as it would have been a complete one off from what was asked of the outside backs in all other matches in the selection. Whether by design or Bernardo’s intuition, this did present another option for Leipzig to create a back three when faced with a higher first line of pressure with two players.

Using a back three in this manner might be a tactic for RB Leipzig to employ when ahead in matches. There were times they were caught out pushing for a goal to go two up and kill the game off only to concede by being hit on a counter. Both outside backs in advanced positions carries a significant threat to the opponent as Leipzig will attack with eight players, it also leaves them vulnerable and asks a lot of the center backs. When discussing Leipzig’s defensive approach you’ll see more of how what makes them a threat in attack, leaves them exposed at the back. This isn’t to suggest a deviation from Leipzig’s approach, but a slight touch of conservatism when ahead, like keeping an outside back in line with the center backs when ahead, may gain them some points in the second half of the season.

It could also be argued just as strongly not to change the approach that one’s used to get the lead in the first place and if you are up a goal, the best way to defend it is to go up by two. RB Leipzig and Hasenhüttl clearly favor the brave approach to protecting a lead.

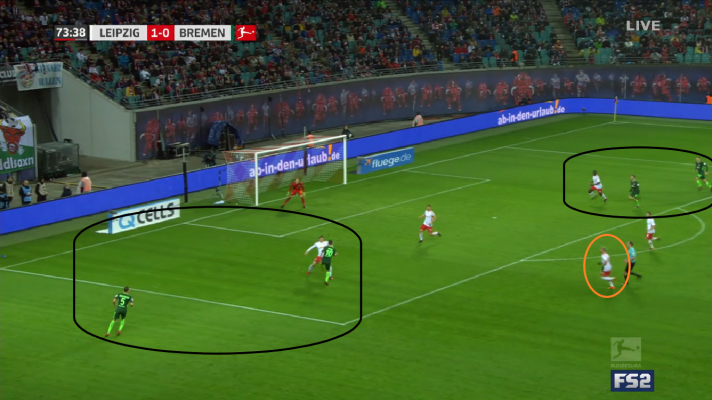

Bernardo may have displayed an ability to play a conservative role against Mainz in organized attack but he displayed the same propensity to get forward later in the same match as his fellow outside backs. The picture below shows Bernardo on the verge of controlling a loose ball from a Leipzig throw in. He is well within Mainz’s half and over to the right side of the field. From here he plays forward to Bruma(the left advanced mid) and then overlaps him with a run into the right half space, as Bruma was moving right to left, this is perfectly understandable. Bruma flicks the ball back to Bernardo who rifles a shot from twenty-five yards on target. The left outside back shooting from the right half space, not a commonality in the game of soccer.

It does show Leipzig’s determination to create overloads around the ball, in this picture we also see that the two left sided players, Bruma and Bernardo, come into play to create a 7v6 against Mainz 05 and then take advantage of the extra man by isolating one Mainz player in a 2v1 resulting in a shot on target.

Klostermann and Halstenberg wind up at the end of plenty of RB Leipzig attacking moves as well. It’s not unusual for either of them to be the furthest player forward and they pop up in attacking situations in a variety of ways. Both are capable of the typical overlap in wide areas to put crosses into the area, though crossing is not a large, nor successful, feature of Leipzig’s chance creation. Poulsen would probably be capable of making use of crosses in the air as he is six-foot-four, however he is usually found in deep or wide positions. Timo Werner is well capable of making runs in behind but due to his excellent dribbling ability, prefers balls be laid into his runs on the ground, not the air.

Both of them were able to adapt to playing with different advanced midfielders with differing tendencies in movement. Bruma spent more time in the left wide area than Forsberg, for example, and Halstenberg was willing to either move deeper or in advance of him and occupy the left half space. When Forsberg spent time in the half space for left sided attacks, Halstenberg made sure to maintain a presence in the wide area, adjusting his height in this space to a deeper position if Werner popped up on the end of the opponent’s back line in the left wide area, a feature of Werner’s movement.

Klostermann did equally as well with Kevin Kampl on the right side, adjusting his positioning deeper when Kampl was already in the right wide area, typically a movement made off of Keïta’s movement into the right half space in advance of his deep midfield partner, Demme.

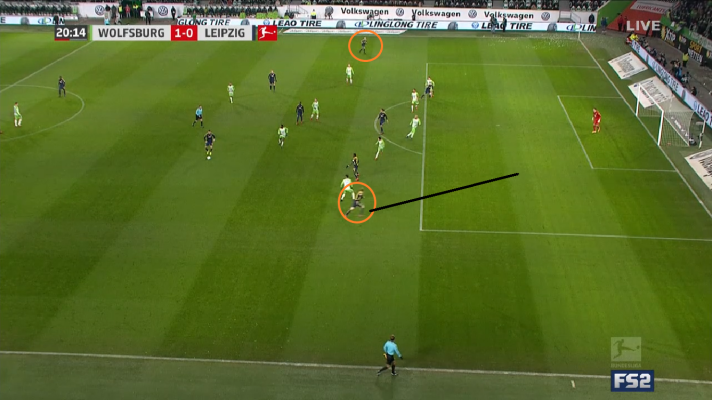

In the match against VfL Wolfsburg, both Klostermann and Halsternberg got on the end of attacking moves.

Off a throw in from the right side in the attacking third, a partial clearance from Wolfsburg falls to Keïta. Keïta plays Werner showing with back to goal, lays off to Keïta who dribbles around two defenders and lays off to Stefan Ilsanker, playing in deep midfield. Ilsanker plays a ball over the top for Klostermann running into the area in the right half space. Klostermann attempts to hit the ball back to Poulsen from the edge of the six but Wolfsburg clears. The run is captured below, where you can also see Halstenberg positioned to make a similar run on the left side.

Later in the second half of the same match, another free run is made. This time it comes from Halstenberg and he takes it upon himself to score with a sliding shot that finds the back of the net. You can see Leipzig have eight players on the right side of the field and only one, Halstenberg, on the left. Poulsen sees what the Wolfsburg players don’t, until it’s too late, as he turns to his right with his back to Wolfsburg’s goal he slips in the attacking outside back.

Player Profile: Timo Werner

Timo Werner is an exciting, young, center forward who is at the beginning of a long and prosperous career at the top of Club and international level soccer. Still twenty-one until March of this year, Werner already has 141 appearances in the Bundesliga and ten caps for the German national team. Werner came up through VfB Stuttgart’s system, making his first team debut on August 1, 2013, at seventeen years of age, in a Europa League qualifier.

In three seasons with VfB Stuttgart he became the youngest player to make fifty Bundesliga appearances and scored thirteen goals in ninety-five league matches. Werner then joined RB Leipzig in June of 2016 and has been with them for both their Bundesliga campaigns, including the current one. His goal scoring rate has taken off since the move to Leipzig, scoring twenty-nine times in forty-six Bundesliga appearances. Overall, he already has forty-seven goals in 159 Club appearances across all competitions.

In the summer of 2017, Werner was a member of the German team that won the FIFA Confederations Cup in Russia. He scored his first three goals for his country in the competition, netting twice against Cameroon and once against Mexico. He’s since won caps in FIFA World Cup qualifying matches and in a friendly against France, scoring a further three goals.

Werner is an absolute delight to watch in Leipzig’s attacking moves. He has an excellent ability to dribble at pace with the ball under control, make runs in behind a back line, provide width in advanced positions, finish his chances and coolly bury penalties. When he’s on the ball in wide areas he’s equally adapt at taking a player on 1v1 or crossing to a teammate. If required he can drop deep and get involved with the attack in deeper areas and is a willing worker in defensive duties.

How long RB Leipzig will be able to keep hold of him will be a test of the type of Club they have ambitions to be. Every other Club in the Bundesliga is beholden to the supreme financial and successful behemoth that is Bayern Munich. If Werner were playing for BVB, it would be a matter of when, not if, he would join up with the giants from Bavaria. Will Leipzig be able to stand up to them? Surely they have the financial ability to match Bayern’s wages, if they want. Qualification for the Champions League for a second year running will probably be a key factor in keeping Werner, and others.

Werner’s ability to be effective on the counter, dart in behind a deep back line and attack from wide areas makes him attractive to nearly any team in Europe. It may be a waste of his goal scoring ability but he could certainly play a wide forward role just as easily as a central one, he essentially does both at the moment for Leipzig already. He fits in perfectly though with Leipzig’s attacking style and is an exciting player to watch in an exciting team. For supporters of RB Leipzig and attack minded soccer, hopefully he sticks around for a bit longer.

Attacking from the Front: Timo Werner and Yussuf Poulsen

Both of RB Leipzig’s preferred front two, Timo Werner and Yussuf Poulsen, are young and talented attacking players. They also function well together and seem to have developed a strong understanding of each other’s preferred movements. Rarely are they both occupying the same space or performing a redundant task. Their ability on the counter attack is exceptional, and they’ve had to adapt to being denied those opportunities along with the rest of the team this season.

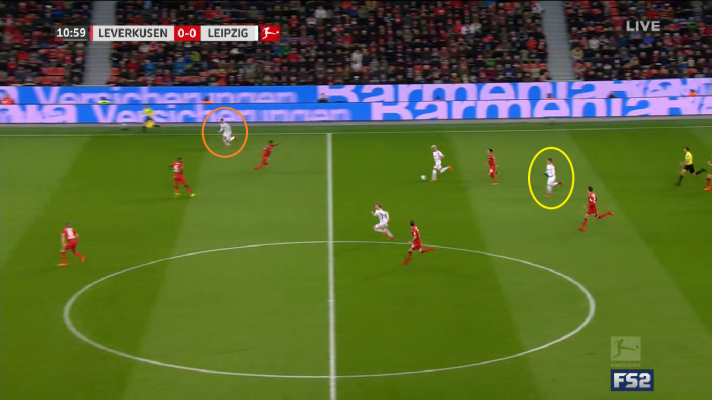

Not only were their counter attacking chances limited, opponents were keen to break these situations up with cynical fouls. Both Poulsen and Werner’s tight control while dribbling allowed them to beat players, only to be cynically fouled. However, Leipzig were able to win free kicks, penalties(three), and corners from counter attacking situations. In their 2-2 draw with Bayer Leverkusen, both goals were scored on penalties, one was the direct result of a counter attack, the other was a hand ball in the penalty area from a free kick won by Werner on a counter.

The first penalty was won by Marcel Sabitzer, who was slipped a pass from Werner at the corner of the penalty area, Werner was played in behind by Kevin Kampl just inside Bayer’s half, dribbled down the wide area, cut inside, allowed Kampl to run beyond him and played Sabitzer, trailing the attack, who was taken down for the penalty. The picture below will show Werner in a favored area of his, in the advanced wide area, a position he would take up in both counter and organized attacking periods.

In the second half, Werner is back helping defend in and around Leipzig’s penalty area, a partial clearance comes to him in the right half space and he dribbles, about, forty yards in seven seconds, takes three Bayer players with him, stops his dribble briefly, realizing he has no support and is 1v3, before winning a foul after starting his dribble again. Werner was livid for being taken down so cynically but the resulting free kick resulted in a penalty and a 2-1 lead.

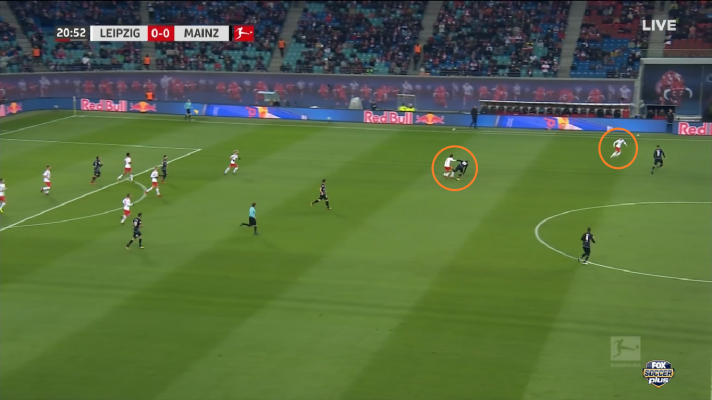

Poulsen or Werner were happy to counter attack alone but were at their best when able to counter attack as a pair. As mentioned previously, this often meant attacking in down numbered situations as opponents were careful to safeguard against Leipzig’s counter attacking play.

Below, is the start of what winds up being a 2v5 counter attack from Poulsen and Werner. In the frame, Poulsen is just about to win the ball and beat his direct opponent, while Werner is beginning his run. Poulsen winds up dribbling into Mainz’s half, pulls three Mainz players to him and then slips a pass beyond Werner and a Mainz player. Werner is initially further away from the ball than the closest Mainz player, however, his excellent pace allows him to get to the ball first, dribble down to the goal line and flick the ball back to Poulsen. They don’t create a chance off of this directly, as the flick back to Poulsen is just cleared away, however, Leipzig controlled the clearance and were able to begin a more organized attack deep within Mainz’s half.

Werner and Poulsen’s positions when RB Leipzig did not have the ball and were defending in organized play usually saw them flat and close together performing their defensive duties, not dissimilar to many front pairings across top level soccer. In attack, Poulsen and Werner were effective in mimicking attacking positions normally taken up by wingers and center “attacking” midfielders, two positions Leipzig play without.

Werner’s movements into the wide areas were not random, he moved into the ball side wide area, whether that was the left or right, didn’t matter. When he did, Poulsen, generally, stayed in a central position. What they were creating was a winger and center forward arrangement, similar to what a front three would create. Essentially, they were trying to act like a front three with only two players. The extremely high positioning sometimes taken up by the opposite side outside back would fill the space occupied by the opposite sided winger in a front three, or thereabouts.

The above example is just one way RB Leipzig would look to play through one side of the field. Poulsen would also move into the half space where Forsberg is and then Werner would be the one to stay central. In attacks coming through the center of their opponent’s half in organized phases, Werner was more likely to stay high with Poulsen dropping into the space in front of the opponent’s back line.

All very fluid in reaching the situation of overloading their opponent, creating multiple forward passing options for the player on the ball, maintaining a forward to occupy the opponent’s center backs, an option behind the center forward, and one player in a position for an opposite sided attacking run. These would all be consistent elements of Leipzig’s attacking play, the variety came from different players providing these elements in certain areas of the field and the characteristics of the player selected.

Attacking Play Overview

RB Leipzig slumped into the winter break both in the Bundesliga and in the Champions League as they have dropped out of that competition and are into the knock rounds of the Europa League. Leipzig’s players have had to make two difficult adjustments this season, the adjustment of their opponent’s to them and the extra demands of European soccer.

Six midweek games added on top of the Bundesliga schedule in the fall took a visible toll on Leipzig in multiple games across this selection. It also had an effect on player selection which added a poorer understanding among the players to go along with the fatigue. The youth of the team amplified this situation as well, they wouldn’t have many players used to the demands of the schedule nor opponent’s being determined to stop them from being successful in counter attack play.

Leipzig did display the ability to move into deep attacking situations in organized attack throughout the selected matches, only for the final ball to be inaccurate or a run just slightly mistimed and opponent’s with large numbers back to clear their advances into the penalty area. The pragmatic recommendation would be to adjust the style, open up more, circulate the ball with more switches of play and bring the outside backs deeper earlier in attacking moves. The youthfulness of the team, however, lends to a simpler approach of staying the course. As they gain more experience, both in how they must play now and the rigors of their schedule, the effectiveness of their organized attacks should improve.

As we will see in part three, the more pressing area where progress is needed and a cutback in mistakes from youthful exuberance is when RB Leipzig are not attacking. That’s where all their full throttle eight players into the attack, fluidity, roaming advanced mids, and outside backs finishes chances causes all sorts of excitement when the ball starts going towards their own goal, not the opponents.

RB Leipzig’s defensive problems correlate strongly to their attacking characteristics. They find themselves giving excellent counter attacking opportunities to their opponent’s trying to overcome being denied this themselves. Leipzig relish their opponent coming onto them in numbers in deep positions to launch counter attacks but it has them scrambling back to protect their goal more often this season. Some of their defensive tactics further compound the problems their attack play creates as well.

In organized defensive situations, Leipzig were usually effective in stifling their opponent’s progress deep into their half. Six of the twelve goals conceded were the result of opponent’s counter attacks. The other six were nearly all down to individual errors or lapses in concentration. The actual tactics employed in organized defending themselves were quite effective.

Leipzig mostly faced back threes in the seven analysed matches. In most instances they would mark up 3v3 on opponent’s goal kicks to force them long. When their opponent established control of the ball inside their own half, from a throw-in, restart, or ball circulation while getting their shape, Leipzig would setup in the 4-2-2-2 shape.

From the above positions, Leipzig would press when one of the two outside center backs received a pass, 3v3, either looking for a clearance or a pass back to the keeper, which they would press with a center forward. When an outside center back opened up in the right wide area, Forsberg would press along with the center forwards. When required to bring a third player forward to stop the opponent from playing out on goal kicks, an advanced midfielder would join the center forwards.

If the opponent moved their organized attack into the midfield third, Leipzig’s advanced midfielders would then look to mark a ball sided player in the wide area. The intent seemed to be deny advancement down the wide areas, force play back or into the center where the deep midfielders would look to win the ball. The advanced midfielders looked to prevent the possibility of them getting beaten off the dribble which would allow for a 2v1 against the outside back and ideal crossing situations for their opponent.

Some teams do just the opposite and allow for the pass to go into the wide areas and it serves as a pressing trigger with the intent to use the touchline as a ‘defender’ and lock their opponent’s attack into one side of the field. It’s understandable though why Leipzig wanted to avoid this, for one, none of Emil Forsberg, Bruma, or Kevin Kampl are particularly strong 1v1 defenders, secondly, RB Leipzig’s compactness leaves them susceptible to deep switches of play, and lastly, they don’t deal well with crosses into the penalty area. They much preferred to win the ball back in higher positions or centrally to then use their pace, technique and vertical runs for counter attacks.

When pushed deeper into their own half, Leipzig flattened out into more of a 4-4-2 and were less susceptible to quick switches of play as the advanced midfielders were better positioned to assist their sided outside back. This was not a common enough trait in most unorganized defensive phases or when pinned into their own penalty area.

Exposed in the Wide Areas

One of the issues caused by Leipzig’s attacking play that presented defensive problems was the central movement of the advanced midfielders. That allowed for opponent’s to create 2v1s in wide areas deep into Leipzig’s half, excellent crossing positions, that they struggled to stop. The simple logic is if you are going to allow crosses to come in, you better be able to deal with them, if not, then you better stop the crosses in the first place. Leipzig weren’t able to consistently do either.

The crosses they faced weren’t always lofted balls into area, often, because of the time afforded, low driven crosses to specific attacking players were picked out. That Leipzig didn’t concede even more goals from these situations was due largely to last gasp individual defensive efforts or poor finishing from their opponents. Not the most sustainable of approach going forward.

It was bad enough for the outside backs to be left either in a 1v1 in a huge space for the attacker to exploit or a 1v2 in the wide areas, but that was actually a better situation to what commonly occurred in the wide areas. No one was there to defend. When one of your left sided players is in the center of the field in advance of the ball and the other is thirty yards beyond the center backs, it’s leaves a massive space for the opponent to counter attack into. When Leipzig’s press was beaten or they turned the ball over, their compactness quickly turned into a major problem as a simple switch of play would cause panic across the team.

A further complication with situations in the wide areas was Leipzig were often 2v2 with their center backs and the opponent’s forwards. This left the center backs with difficult decisions of whether to come out wide and close down the attacker on the ball or stay central with their forward. The youth and inexperience of two of Leipzig’s regular center backs, Dayot Upamecano and Ibrahima Konate, added stress and volatility to these situations. A tremendous learning curve for the two young backs to be breaking into a top Bundesliga side, competing in the Champions League, all the while being thrown into desperate defending situations.

Player Profile: Dayot Upamecano

Dayot Upamecano just turned nineteen in October of 2017 and joined RB Leipzig in January of 2017. Previous to that he broke into first team soccer with Red Bull Salzburg, joining the Austrian outfit in July of 2015, having never made a first team appearance in his native country of France. Upamecano spent his youth career in France, the last two years where spent with Valenciennes FC’s youth program.

He has yet to make his debut for the full French national team, having made thirty-one appearances with French underage national teams. Upamecano played in all six matches for France’s UEFA European Under 17 Championship winning team in 2015, while being selected for the team of the tournament.

Upamecano is a six-foot-one center back who’s shown immense progress for Leipzig thus far in the 2017-18 season. Along with Imbrahima Konate, he’s made some costly mistakes for Leipzig as part of his learning experience. He’s also shown flashes of superb 1v1 defending, is an exceptional tackler and makes good use of his strong, physical presence. Calm and willing to play with the ball at his feet, Upamecano has the potential of developing into a top level center back in the near future. Leipzig have certainly been prepared to let him develop and play through his mistakes on a regular basis with the first team, he has thirteen Bundesliga appearances this year and turned out five times in the Champions League group stage.

Ensuring Chaos: The High Back Line and Offside Trap

Just in case the exposure in the wide areas and the youthfulness of the center backs wasn’t enough, RB Leipzig played with a daringly high back line, allowed backs to step out of that line to gamble on tackles and interceptions and while they were at it, routinely tried to catch opponent’s forwards in offside positions by stepping forward as they made runs in behind. This all produced plenty of chances for opponent’s attacks and caused Leipzig real problems.

The high line itself is a necessity for pressing teams as the back line must push up to make the field as small as possible for the pressing players in front of them to win back the ball. When the midfield and forward’s pressing actions were beaten the back line was not quick to drop off, instead they would routinely press themselves. It should be said this did sometimes come off, the ball was won back and Leipzig were gifted an infrequent moment of poor organization from their opponents to counter. The best example being the previously referenced opening goal against Werder Bremen.

When this did not succeed, their opponents were gifted ample attacking space to take advantage of. Then all of their other issues would begin to sprout up.

Here are some descriptions of goals conceded by Leipzig:

First Goal conceded against Hannover 96:

Quick ball into a center forward catches Leipzig 2v2 with their center backs and Hannover’s forwards as Halstenberg was caught out pressing, quick combination play caused confusion on marking between Upamecano and Konate, leaving center forward free in a central area, slots home opener. Watch the end of the attack, here, you can see Konate and Upamecano manage to both not get tight to the player on the ball, nor mark the central attacker.

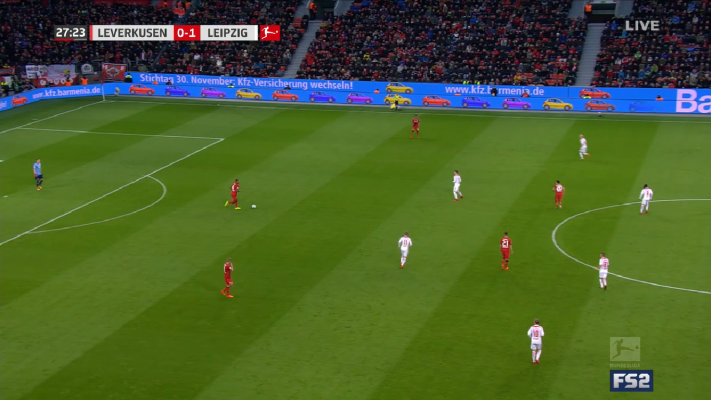

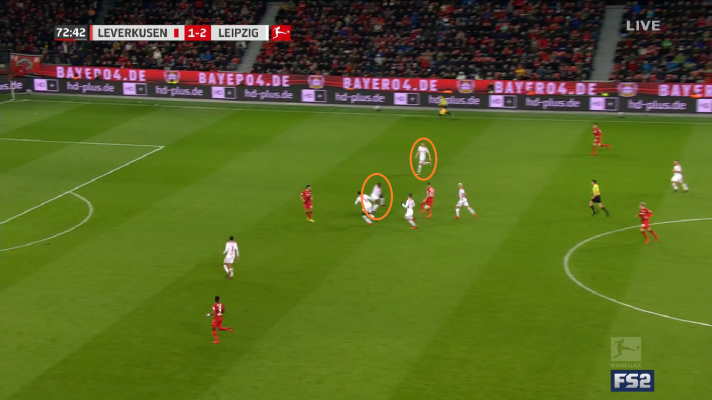

Second goal conceded against Bayer Leverkusen:

Leverkusen are into Leipzig’s half in the left half space on a counter. Upamecano steps out in an attempt to tackle, gets beat, Halstenberg gets beat to his outside after, then the two nearly collide and have a visible confusion between the two allowing the attacker to drive forward and slot in a cross cleared for a corner. Leipzig concede on the ensuing corner.

First goal conceded against Mainz 05:

Willi Orban and Bernardo both get caught level with Mainz’s attacking player making a run in behind. Even if they had caught him offside, Stefan Ilsanker was deeper and playing him on anyway. The pass comes to the attacker who has both Orban and Bernardo beat, leaving Ilsanker having to come over and attempt to cut across the attacker. Ilsanker misses the ball and takes the attacker down for a free kick(after VAR review). Another example of the high line leaving backs exposed.

The Sum of All Fears: Hoffenheim 4 RB Leipzig 0

Nothing short of an outright disaster was the result of Leipzig’s trip to Hoffenheim. Julian Nagelsmann laid out the perfect game plan to stop RB Leipzig and his team comprehensively tore them to pieces. It was the perfect setup, an ultra compact 5-3-2 denied space in behind, denied counter attacking opportunities, and they were impervious to being played through when Leipzig attacked in organized situations.

Sometimes in setting up to defend against the opponent’s qualities you leave yourself with no way to attack yourselves. As the scoreline suggests, Nagelsmann left plenty to offer going forward. The main component was the two center forwards causing problems for Leipzig’s center backs. The other was their compactness allowed them to spring forward quickly similar to how Leipzig prefer to counter themselves.

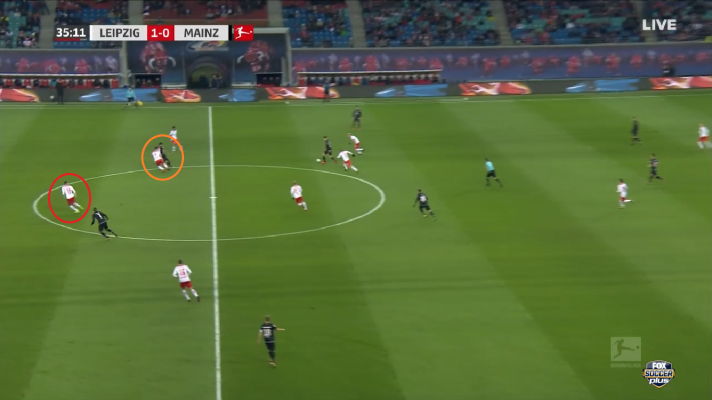

The second goal was conceded as a direct result of a failed attempt to leave an attacker offside on an attacking run in behind. It didn’t come off and that’s why as the video shows, Gnabry was as free as he was in behind. See the picture below.

The lob from forty yards as the video shows was the result of an unusual turnover in a poor position from Werner, much deeper than usual, trying to play centrally into the center circle. The center back pairing is too far from Gnabry to do anything and Gulacsi is caught out in this unexpected moment.

It was a painful experience for Leipzig and not one they recovered from well, as they proceeded to limp into the winter break with two draws and a loss in the Bundesliga.

Overview when Defending

Where Leipzig have struggled in creating chances from organized attacks, they have mostly excelled in defending their opponent’s organized attacks. It creates a conundrum for Leipzig, they want an open game, with many unorganized situations with stretched opponents to score goals but leak goals all the same when able to open the game up.

Leipzig want to press and force the issue in the opponent’s half to create chances if they cannot stretch their opponent and get them to commit numbers forward. But in this zeal to press, which their opponents know is coming, they leave themselves vulnerable when the press is beaten. Their compactness in attack is bold and determined to break through the opponent, they’re not much interested in going around or over the opposition, but again, this puts them into dangerous situations when the ball is lost.

They gamble even more with their high line, offside trap and the backs willingness to step forward for interceptions and tackles. It requires bravery, focus and energy from the whole team in all moments of play. Full belief and commitment to the cause can’t be judged from afar but Ralph Hasenhüttl will know if he has that from his players, he needs it from all of them, in every situation, in every match.

Hasenhüttl will show in the second half of the season how brave and committed he himself is. He couldn’t be faulted for a more conservative approach going forward, tracking runs instead of the offside trap, less attacking and gambling on interceptions from his outside backs, spacing out more in attack to prevent getting exposed in wide areas and so on. Or, he could choose to be as brave as he asks his players to be and show belief in them, that they will develop as a young squad and less mistakes over time will sure up their defending and empower their attack.

It’s not an easy decision for a coach to make and only Hasenhüttl will know how much pressure is on him to achieve certain targets. And he, and everyone, knows that if his approach to reach those targets doesn’t succeed, he’ll get the sack, not the players he has asked to believe in him. He’ll need to be able to trust his approach and trust his players if RB Leipzig are to continue with their bold and exciting brand of soccer.

For a team owned by an energy drink, RB Leipzig have, inadvertently, gone to the extremes in matching their playing style with Red Bull’s brand identity. Along with Red Bull’s Formula 1, air racing, motocross and other extreme sports teams, Ralph Hasenhüttl’s RB Leipzig fits right in alongside them all, wings or no wings.

Part Four: Application at Youth Soccer Level

RB Leipzig’s way of playing under Ralph Hasenhüttl would provide an excellent learning experience for youth players. Every aspect of their play demands high concentration levels from all players at all times. Whether the team has the ball or not, players would need to be prepared for almost any eventuality at a moments notice. Lapses in concentration would be punished harshly by opponent’s counter attacks or brief opportunities to advance the attack would vanish with only a moment’s hesitation to play a pass or move into an area of the field.

Every player would need to be comfortable with the ball, willing to receive in tight spaces, pass into tight spaces, take players on and work hard off the ball to fill the correct spaces for forward passing angles. It would be difficult to exist in a team emulating Leipzig’s style without a willingness to diligently perform defensive duties as well. The coach would also need to prepared to have a high level of patience with their team as an acceptance of mistakes as part of the learning process would have to be present.

The players and parents would certainly need a good deal of communication from the coach as well to ensure there is an understanding between everyone in the group that the objectives of player and team development will benefit from what otherwise might look like the approach of someone who’s lost their mind. An acceptance and willingness would need to be present from the players that, yes, they will make mistakes, and that’s not a problem because those mistakes will push their development forward.

Hasenhüttl cuts a calm figure on the touchline during games and even though he’s coaching at the highest of levels, this would be required of the coach as well. The coach would need to show, as well as preach, acceptance of mistakes.

The best part about playing in this way is the players will enjoy it. The coach is pushing them into attacking situations, encouraging them to be aggressive, allow them to express themselves and letting the players make their own decisions. Again, looking at Hasenhüttl from afar, it seems that his players know what he expects but the fluidity of their attacking play shows he trusts them to figure out how to carry out his principals and he allows for their individuality. Bruma and Forsberg both played at left advanced midfield but didn’t play it in the exact same way, others around them were willing to adapt their play to let these two try to influence the match in their own way.

And for a coach who wants players to unlearn what too many learn early on about what “defenders” do and “strikers” do or ask to play on offense because defenders “just stay back”, getting outside backs finishing attacking moves and nearly always looking to step forward, not back, when the ball is lost, is a great way to change this mentality.

The compact organized attacking play would be of good use to younger 11v11 teams, especially at the U13 and U14 levels. These players are often asked to play on the same size fields as high school and college age players while themselves being far smaller. It’s not a necessity with these younger teams to open the field up as much as possible in attack as they often don’t have the physical ability to take advantage of all the space they can create. Yes, opening up with two players in each wide area creates space to play but it can also slow the game down. Switches of play from side to side take longer to execute and the vertical space between the lines can become stretched when twelve year olds mimic the positioning of adults.

If the players don’t need all the space they create and it slows down the game, it expands time for decision making and gives players more room for 1v1 situations. At the top level of the game, where winning is all that matters, that’s a good thing. But at youth level, development is the key goal. Then the idea should be give the players just enough space to play but not too much space where ball control and decision making don’t need to be as sharp. Players will initially lose the ball more or play more poor passes, yes, but the environment will force quicker decision making and players will become more adept at ensuring they get a good touch on the ball.

Nearly every coach at youth level believes in the above, tight spaces and small sided games are a great development tool. Why then do we need to put this tool away at the weekend? As the players get older and grow, you as the coach can gradually guide the team to spread out more in attack. When they reach full maturity you might then decide to implement attacking play to make the field as big as possible. But then again, all of RB Leipzig’s players are at full maturity and play in this fashion anyway.

The 4-2-2-2 formation does not need to be utilized for any of the above, it’s much more the mentality of the team developed by the principals given to them by the coach. However, there is a benefit to using this formation. It’s benefit is actually it’s biggest drawback in attack, it doesn’t lend itself to easily creating correct passing angles to create triangles and diamonds. The 4-3-3 is a wonderful teaching tool because of it’s flexibility. The 4-2-2-2 has a usefulness as a teaching tool because it requires flexibility from the players to create proper passing angles and structure.

All of the relationships developed by the RB Leipzig players between one another foster a good understanding of the effects of their movements to the rest of the team. The team needs to adapt to each other’s positioning to make sure certain spaces are occupied. Diego Demme and Naby Keïta developed an understanding that if one of them moved into an advanced position, the other would remain deeper, or if one moved into the half space, the other would stay centrally. Kevin Kampl and Lucas Klostermann understood one of them needed to be in the right wide area for right sided attacks and the other needed to be in the half space if it wasn’t occupied by Yussuf Poulsen. Poulsen and Timo Werner’s movements to mimic wing play or filling in space behind the center forward while the other took up a more natural center forward position.

All of the above need to be developed to ensure the team breaks out of the defensive shape and into an attacking shape able to play through their opponent. It’s a great way to encourage players to play within a structure without feeling like their in a structured environment.

Hopefully everyone who’s taking the time to read this will have gotten something valuable out of it. For coaches, I hope you can use something here in your coaching going forward and it turns out to be of benefit to your players. For anyone interested in RB Leipzig, I hope you enjoyed the read and feel a deeper understanding of how this team plays. Leipzig were a great choice for a project that’s consumed a great deal of time over the last three weeks and would love any feedback you have to share!